I don't know where to begin with this one. It's another in the line of recent so-called indie rock memoirs that have been reviewed on Flying Houses, after Bob Mould, Carrie Brownstein, Patti Smith, and Kim Gordon. Morrissey is a bigger star than all of them, and his Autobiography is much longer. Stylistically it is also much more unique.

A quick word about my relationship with Morrissey: I love him, and have enjoyed his music since the early-to-mid aughts. I would have to pinpoint You are the Quarry as the moment when his music began to take on a bigger role in my life. I have pretty much the whole Smiths catalogue on my iPod (with the exception of Rank) and I have a few Morrissey albums--but something extremely curious has happened: most (almost all) of the Morrissey solo material (excepting Years of Refusal) is no longer playable on my iPod. The songs still exist, but the iPod freezes up, and the songs get skipped. No more "Suedehead" for me, nor anything off of Quarry. I almost feel like the iPod has become self-aware, as the lyrics change on the Live at Earl's Court recording of "Bigmouth Strikes Again" from Joan of Arc's "Walkman" starting to melt to "iPod." Apple fears Morrissey, and would rather silence him.

Now perhaps Moz himself would find this ridiculous (that a machine denies his music to me), but I would like to think he finds it rather amusing, because so much of Autobiography concerns itself with little ironies such as this: Morrissey is great, and everyone knows he's great, but he is still perpetually misunderstood and maligned regardless, singled out for his accomplishments, perhaps out of envy or the cruel nature of humanity. He's too effete or he whines too much or he's too self-obsessed and people just don't give him the respect he's due--nobody except the fans, that is.

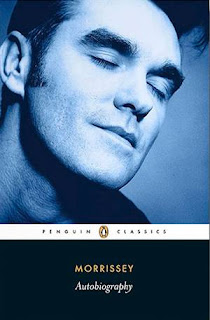

But back to the book itself. The most striking thing about this book, without question, is its structure, or lack thereof. I cannot remember the last time I read a book that had zero chapters breaks, whose separation only came in the form of paragraph breaks or an extra space between paragraphs, so this may be the first. In other words, it is not an easily digestible volume, and I feel this is done for stylistic reasons that go along with its unusual cover, which make it appear as if it truly is something from the Great Books canon, perhaps like an edition of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein for use in a high school or college curriculum. In form, it resembles 19th century literature. Truthfully, there are many more music courses in college and I am sure this book could end up on a couple college reading lists. At the very least, it sheds light on the oft-explored issue (on VH1's "Behind the Music") of the hapless musician faced with contracts he or she cannot comprehend, and the swindle carried out by record companies:

"...In time-honored tradition, we were just two more pop artists thrilled to death with the spinning discs that bore our names. The specifics of finance and the gluttonous snakes-and-ladders legalities were deliberately complicated snares that all pop artists are expected to understand immediately. The act of creating music and songs and live presentations are relied upon to sufficiently distract the artist so that labels and lawyers and accountants--so crucial to groups in matters of law--might thrive. It is nothing new. The basic rule, though, is to keep the musician in the dark at all costs, so that the musician might call upon the lawyer repeatedly. In fact, pop artists live in a world that is at a dramatic distance from the world of commerce, and they are usually exclusively consumed by their gift or drive at the expense of everything else. A vast industry of music lawyers and managers and accountants therefore flourish unchecked due to the musician's lack of business grasp. Thus, any standard recording contract deliberately reads like ancient Egyptian script--surely in order to trick the musician. Rather than hide your face under the bedcovers, you are thus forced to do business with those whom you least mind ripping you off--chiefly because you have no choice, and also because the law insists upon a documented trail of every penny that you earn--mainly so that someone might take it from you. The artist is the enemy. Solicitors are trained to squeeze as much money out of their client as possible, and accountants might deliberately steer their client into tax troubles so that those very same accountants are further needed to unravel the mess that they created in the first place..." (170-171)

The other reviews I've seen of Autobiography are predictably polarizing. On the one hand, most recognize that this is not a perfect memoir, but there are occasional flashes of brilliance. On the other, many profess that it is in dire need of a strong edit, and no one will fail to mention the 1996 Smiths Trial. Now personally, for me, this was the best part of the book. It just kept going, and going, and going, and I thought it would go on until the book ended. At first I thought it was ridiculous that he would spend 25 pages discussing this trial in sharp detail. It actually ends up going on for 50 pages.

But before we get there, we have to hit on the first target of Morrissey's ire: Geoff Travis, the "moral conscience" of Rough Trade Records. There are about two anecdotes where Travis comes off well (an extremely complimentary letter on The Queen is Dead stands out); at every other mention he is skewered. Perhaps there is no funnier moment than when Travis says, after hearing "How Soon is Now?" for the first time, "WHAT is Johnny doing, THAT is just noise." (178) then later proposes it as the A-side to "Shakespeare's Sister" B-side. But that has been quoted on other various sites. I can't find the quote I'm thinking of, but this is the second time Travis removes his glasses:

"Geoff leans forward and removes his glasses. 'Do you know why Smiths singles don't go any higher?'

I say nothing because the question is horribly rhetorical.

'Because they're not good enough.' He puts his glasses back on and shrugs his shoulders. I glance around his office searching for an axe.

Some murders are well worth their prison term." (207)

I think he says something arguably more offensive the first time he removes his glasses, which Morrissey says he does when he is about to relay some harsh truth.

The opening of the book feels "Dickensian," befitting the Penguin Classics imprint, and all of the material about his childhood seems to be written at more of a distance than the material about his career. In general I have to say that this is not the most enjoyable book to read, but that fans of Morrissey (of which there are very many) will find it irresistible. Maybe I am not a big enough fan to truly "get" it, but I found much of the book charming. I really do not think this book sheds light on many situations that casual fans might ponder. Morrissey is well aware of his mythological status, and he plays with it throughout the book to amusing effect, particularly with references to his romantic life.

Many people believe that Morrissey is celibate or asexual or gay, or some variant, but it appears after taking everything in this book together that he is bi. This is mainly because he writes of a few relationships that turned into quasi-domestic partnerships, two with men and one with a woman whom he nearly had a baby with. I don't want to dwell too particularly long on this topic, but there are some amusing passages on these times.

However, we should continue the recent trend on Flying Houses of quoting passages about Patti Smith (Patti Smith is turning into the "topic of the year" on this blog, as nearly every book reviewed seems to reference her in some form or another, a testament to her incredible influence):

"....Cross-legged by a dying fire later that night, and with only a side-light for company, I allowed Horses to enter my body like a spear, and as I listened to the bare lyrics of public lecture, I examined the genderless singer on the heavyweight album sleeve. So surly and stark and betrayed, Patti Smith was the cynical voice radiating love; pain sourced as inspiration, an individual mission drunk on words--and my heart leapt hurdles, scaling and vaulting; something won and overcome. Unfulfilled as a woman, impotent as a man, Patti Smith cut right through--singing and looking and saying absolutely everything that would be thought to go against the listener's sympathy. But the reverse happened, and the wisdom of centuries shook me and told me that, however heavy-hearted and impossible you might feel about yourself, you can still bestow love through recorded song--which just might be the only place where you have the chance to show yourself as you really are since nothing in your disposed life gives you encouragement. The fact that you do not look like a pop-star-in-waiting should not dishearten you because your oddness could become the deciding wind of change for others. There is nothing obvious about Patti Smith, least of all any obvious biological conclusions, and this gives its own erotic reality in a shyness of arrogant pride. The past snaps. I have never heard or seen anything like Patti Smith previously, and I have never heard truth established so sincerely. The female voice in rock music had rattled with fathomless depths of insincerity, whereas Patti Smith spoke with a boy's bluntness, and she looked for squabbles wherever she went. Horses pinned all opponents to the ground. It shook the very laws of existence, and was part musical recording and part throwing up. Its discovery was the reason why we could never give up on music, and its effects were huge..." (111-112)

As others have noted, Morrissey is not so revealing about his own music as he is about other artists. That is, his modus operandi or r'aison d'etre can be explained through the observations he makes of other artists, and that is no more true for me than here. Perhaps one could say what Patti Smith means to Morrissey, Morrissey means to me. The true power of art is inspiration.

So it comes as a pleasant surprise (in what will surely be an annoyance to most) that Morrissey is OBSESSED with the legal system. It is almost like he has been through the wringer so many times that he might as well be a solicitor himself. I believe that the section of the book on the 1996 Smiths Trial is so protracted specifically because Morrissey wants everyone to know all the tiny nuances of the case to see just how rank an injustice was done. Long story short: Michael Joyce and Andy Rourke, drummer and bass player in the Smiths, were basically paid 10% of the total earnings from the Smiths, and Morrissey and Johnny Marr, the principal songwriters, were paid 40%. Aspersions are not cast on Rourke so much as Joyce. Joyce asserts that he should actually receive 25% of the proceeds, and that he just "assumed" it was an equal partnership between the four. Despite having zero proof, Joyce ends up winning, and Morrissey is absolutely miserable. Now this could be a point where anyone can turn on the author, because let's admit that he has been allowed to have a fabulous life where he does not need to worry about money. But it seems like the principle of the thing. He's getting taken advantage of because people don't like his attitude. At least that's what it seems like from everything said about the judge. It will be impossible to pick out the best passage from this lengthy section, but here is a representative sample. Keep in mind that the reason almost every single review considers this the chief failing of this book is because it is repetitive. (And to reiterate, I do not feel this is a failing at all):

"Three words were used that had never previously described me, thus their weight as a catchphrase for eternity. Had Weeks described me in words befitting my character, no would care or give any attention. The meaning of 'devious, truculent and unreliable' is to present a description so patently unlikely that ears prick up. We all know that, if repeated often enough in print, words are bound to eventually be believed, and it seemed obvious his quote would indeed be printed enough. In the event of any future court action shading my life (fame = money = lawsuits), the 'devious, truculent and unreliable' stinger alone need only be used once by any opposing party and my defense would come unstuck, because 'devious, truculent and unreliable' in judicial parlance means 'evil, aggressive and a liar'. What was the reason for this attack on me, so aggressively fueled and so overdone that it appears to want to bring a life to an end? Surely judges have no need to unleash thoughts that are actually more violent than anything done or expressed by either plaintiff or defendant. What, then, was John Weeks thinking of? In the quiet room of his final years he will be delighted that his potential was realized by a famously recurring quote. It is a quote powerful enough to poison everything. Weeks could have merely said that someone was right and someone was wrong--or, indeed, that both parties were wrong. Instead he leaves a quote that might be rancid and powerful enough to cause one subject to be unable to ever again conduct business; to never again be trusted, or--even better--to kill himself with the brandishing shock of it all. It doesn't take much to force someone over the edge, but Weeks' judgment in itself could have constituted manslaughter." (320-321)

This is my second review in a row that prescribes certain behavior for judges, and again I agree: there's no need for what Weeks did (just like there was no need for me to get "bench-slapped" last month--one day I will go off about the meanness in the legal profession, and how perfectly miserable human beings can make one another for no reason other than the mistaken belief that it's always been done that way, and it's the only way it can work). Morrissey may be whining a bit much about it, but it's true that judicial opinions have "staying power" in a certain sense of the word, and that labeling this particular litigant with these particular adjectives destroys his credibility in any future proceeding. It really is not fair, and Morrissey has every right to spend 50 pages defending his own character through the prism of this trial, even if casual readers may find the section rather long-winded.

In general, this is a long-winded book, and there are so many different things I could mention that this review will inevitably lack something. I do want to say, that, like another famous Irish author, it ends on a stunningly beautiful note. That is, for me personally. And I truly believe that the magic of an artist that one admires comes through in things that mean something unbearably personal to you. And by unbearably personal I don't mean painfully personal--I just mean something that spurs one to believe that the artist is speaking to you directly. There are several references to Chicago (and an especially humorous one about the Genesee Theater in Waukegan, IL) but the final paragraph of the book paints a picture of a scene outside the Congress Theater. This venue is in my neighborhood, and has been closed for several years by the City of Chicago's Department of Buildings, and is now being refurbished to hopefully open in 2017. Actually I was part of the legal team that prosecuted the case against this theater. A very small part, but a part nonetheless. So I feel some ownership over this space, and to see Morrissey end his autobiography on an image outside this theater, where he has just played a show, which must have been one of the last shows held there before the venue was shut down, well it made me smile:

"For a year's-end concert at the Congress Theater in Chicago, the audience heaves with responding kindness, and I am immobilized by singing voices of love.

All along, my private suffering felt like vision, urging me to die or go mad, yet it brings me here, to a wintry Chicago street-scene in December 2011 - I, a small boy of 52, clinging to the antiquated view that a song should mean something, and presenting himself everywhere by way of apology. It is quite true that I have never had anything in my life that I did not make for myself.

As I board the tour bus, a fired encore is still ringing in my ears, and then suddenly a separated female voice calls out to me--full of cracked now-or-never embarrassment above the still Illinois winter atmosphere of midnight, and it was dark, and I looked the other way." (457)

Such a great fucking ending. And you have to love the "still Illinois" line.

Morrissey does that a lot in this book--inserts lyrics or song titles into lines. And there's a lot of alliteration. But as I just mentioned, the real power in this book comes in the multitudes it contains. Everyone will find something extremely personal (like I found in its ending) within it, and the only ones that will fail to be touched will be those that, for whatever reason, are predisposed against the author himself. And why would anyone be predisposed? Because we don't like whiners. But as a whiner himself, I can say that the world has needed Morrissey, and is richer for his presence.

"...In time-honored tradition, we were just two more pop artists thrilled to death with the spinning discs that bore our names. The specifics of finance and the gluttonous snakes-and-ladders legalities were deliberately complicated snares that all pop artists are expected to understand immediately. The act of creating music and songs and live presentations are relied upon to sufficiently distract the artist so that labels and lawyers and accountants--so crucial to groups in matters of law--might thrive. It is nothing new. The basic rule, though, is to keep the musician in the dark at all costs, so that the musician might call upon the lawyer repeatedly. In fact, pop artists live in a world that is at a dramatic distance from the world of commerce, and they are usually exclusively consumed by their gift or drive at the expense of everything else. A vast industry of music lawyers and managers and accountants therefore flourish unchecked due to the musician's lack of business grasp. Thus, any standard recording contract deliberately reads like ancient Egyptian script--surely in order to trick the musician. Rather than hide your face under the bedcovers, you are thus forced to do business with those whom you least mind ripping you off--chiefly because you have no choice, and also because the law insists upon a documented trail of every penny that you earn--mainly so that someone might take it from you. The artist is the enemy. Solicitors are trained to squeeze as much money out of their client as possible, and accountants might deliberately steer their client into tax troubles so that those very same accountants are further needed to unravel the mess that they created in the first place..." (170-171)

The other reviews I've seen of Autobiography are predictably polarizing. On the one hand, most recognize that this is not a perfect memoir, but there are occasional flashes of brilliance. On the other, many profess that it is in dire need of a strong edit, and no one will fail to mention the 1996 Smiths Trial. Now personally, for me, this was the best part of the book. It just kept going, and going, and going, and I thought it would go on until the book ended. At first I thought it was ridiculous that he would spend 25 pages discussing this trial in sharp detail. It actually ends up going on for 50 pages.

But before we get there, we have to hit on the first target of Morrissey's ire: Geoff Travis, the "moral conscience" of Rough Trade Records. There are about two anecdotes where Travis comes off well (an extremely complimentary letter on The Queen is Dead stands out); at every other mention he is skewered. Perhaps there is no funnier moment than when Travis says, after hearing "How Soon is Now?" for the first time, "WHAT is Johnny doing, THAT is just noise." (178) then later proposes it as the A-side to "Shakespeare's Sister" B-side. But that has been quoted on other various sites. I can't find the quote I'm thinking of, but this is the second time Travis removes his glasses:

"Geoff leans forward and removes his glasses. 'Do you know why Smiths singles don't go any higher?'

I say nothing because the question is horribly rhetorical.

'Because they're not good enough.' He puts his glasses back on and shrugs his shoulders. I glance around his office searching for an axe.

Some murders are well worth their prison term." (207)

I think he says something arguably more offensive the first time he removes his glasses, which Morrissey says he does when he is about to relay some harsh truth.

The opening of the book feels "Dickensian," befitting the Penguin Classics imprint, and all of the material about his childhood seems to be written at more of a distance than the material about his career. In general I have to say that this is not the most enjoyable book to read, but that fans of Morrissey (of which there are very many) will find it irresistible. Maybe I am not a big enough fan to truly "get" it, but I found much of the book charming. I really do not think this book sheds light on many situations that casual fans might ponder. Morrissey is well aware of his mythological status, and he plays with it throughout the book to amusing effect, particularly with references to his romantic life.

Many people believe that Morrissey is celibate or asexual or gay, or some variant, but it appears after taking everything in this book together that he is bi. This is mainly because he writes of a few relationships that turned into quasi-domestic partnerships, two with men and one with a woman whom he nearly had a baby with. I don't want to dwell too particularly long on this topic, but there are some amusing passages on these times.

However, we should continue the recent trend on Flying Houses of quoting passages about Patti Smith (Patti Smith is turning into the "topic of the year" on this blog, as nearly every book reviewed seems to reference her in some form or another, a testament to her incredible influence):

"....Cross-legged by a dying fire later that night, and with only a side-light for company, I allowed Horses to enter my body like a spear, and as I listened to the bare lyrics of public lecture, I examined the genderless singer on the heavyweight album sleeve. So surly and stark and betrayed, Patti Smith was the cynical voice radiating love; pain sourced as inspiration, an individual mission drunk on words--and my heart leapt hurdles, scaling and vaulting; something won and overcome. Unfulfilled as a woman, impotent as a man, Patti Smith cut right through--singing and looking and saying absolutely everything that would be thought to go against the listener's sympathy. But the reverse happened, and the wisdom of centuries shook me and told me that, however heavy-hearted and impossible you might feel about yourself, you can still bestow love through recorded song--which just might be the only place where you have the chance to show yourself as you really are since nothing in your disposed life gives you encouragement. The fact that you do not look like a pop-star-in-waiting should not dishearten you because your oddness could become the deciding wind of change for others. There is nothing obvious about Patti Smith, least of all any obvious biological conclusions, and this gives its own erotic reality in a shyness of arrogant pride. The past snaps. I have never heard or seen anything like Patti Smith previously, and I have never heard truth established so sincerely. The female voice in rock music had rattled with fathomless depths of insincerity, whereas Patti Smith spoke with a boy's bluntness, and she looked for squabbles wherever she went. Horses pinned all opponents to the ground. It shook the very laws of existence, and was part musical recording and part throwing up. Its discovery was the reason why we could never give up on music, and its effects were huge..." (111-112)

As others have noted, Morrissey is not so revealing about his own music as he is about other artists. That is, his modus operandi or r'aison d'etre can be explained through the observations he makes of other artists, and that is no more true for me than here. Perhaps one could say what Patti Smith means to Morrissey, Morrissey means to me. The true power of art is inspiration.

So it comes as a pleasant surprise (in what will surely be an annoyance to most) that Morrissey is OBSESSED with the legal system. It is almost like he has been through the wringer so many times that he might as well be a solicitor himself. I believe that the section of the book on the 1996 Smiths Trial is so protracted specifically because Morrissey wants everyone to know all the tiny nuances of the case to see just how rank an injustice was done. Long story short: Michael Joyce and Andy Rourke, drummer and bass player in the Smiths, were basically paid 10% of the total earnings from the Smiths, and Morrissey and Johnny Marr, the principal songwriters, were paid 40%. Aspersions are not cast on Rourke so much as Joyce. Joyce asserts that he should actually receive 25% of the proceeds, and that he just "assumed" it was an equal partnership between the four. Despite having zero proof, Joyce ends up winning, and Morrissey is absolutely miserable. Now this could be a point where anyone can turn on the author, because let's admit that he has been allowed to have a fabulous life where he does not need to worry about money. But it seems like the principle of the thing. He's getting taken advantage of because people don't like his attitude. At least that's what it seems like from everything said about the judge. It will be impossible to pick out the best passage from this lengthy section, but here is a representative sample. Keep in mind that the reason almost every single review considers this the chief failing of this book is because it is repetitive. (And to reiterate, I do not feel this is a failing at all):

"Three words were used that had never previously described me, thus their weight as a catchphrase for eternity. Had Weeks described me in words befitting my character, no would care or give any attention. The meaning of 'devious, truculent and unreliable' is to present a description so patently unlikely that ears prick up. We all know that, if repeated often enough in print, words are bound to eventually be believed, and it seemed obvious his quote would indeed be printed enough. In the event of any future court action shading my life (fame = money = lawsuits), the 'devious, truculent and unreliable' stinger alone need only be used once by any opposing party and my defense would come unstuck, because 'devious, truculent and unreliable' in judicial parlance means 'evil, aggressive and a liar'. What was the reason for this attack on me, so aggressively fueled and so overdone that it appears to want to bring a life to an end? Surely judges have no need to unleash thoughts that are actually more violent than anything done or expressed by either plaintiff or defendant. What, then, was John Weeks thinking of? In the quiet room of his final years he will be delighted that his potential was realized by a famously recurring quote. It is a quote powerful enough to poison everything. Weeks could have merely said that someone was right and someone was wrong--or, indeed, that both parties were wrong. Instead he leaves a quote that might be rancid and powerful enough to cause one subject to be unable to ever again conduct business; to never again be trusted, or--even better--to kill himself with the brandishing shock of it all. It doesn't take much to force someone over the edge, but Weeks' judgment in itself could have constituted manslaughter." (320-321)

This is my second review in a row that prescribes certain behavior for judges, and again I agree: there's no need for what Weeks did (just like there was no need for me to get "bench-slapped" last month--one day I will go off about the meanness in the legal profession, and how perfectly miserable human beings can make one another for no reason other than the mistaken belief that it's always been done that way, and it's the only way it can work). Morrissey may be whining a bit much about it, but it's true that judicial opinions have "staying power" in a certain sense of the word, and that labeling this particular litigant with these particular adjectives destroys his credibility in any future proceeding. It really is not fair, and Morrissey has every right to spend 50 pages defending his own character through the prism of this trial, even if casual readers may find the section rather long-winded.

In general, this is a long-winded book, and there are so many different things I could mention that this review will inevitably lack something. I do want to say, that, like another famous Irish author, it ends on a stunningly beautiful note. That is, for me personally. And I truly believe that the magic of an artist that one admires comes through in things that mean something unbearably personal to you. And by unbearably personal I don't mean painfully personal--I just mean something that spurs one to believe that the artist is speaking to you directly. There are several references to Chicago (and an especially humorous one about the Genesee Theater in Waukegan, IL) but the final paragraph of the book paints a picture of a scene outside the Congress Theater. This venue is in my neighborhood, and has been closed for several years by the City of Chicago's Department of Buildings, and is now being refurbished to hopefully open in 2017. Actually I was part of the legal team that prosecuted the case against this theater. A very small part, but a part nonetheless. So I feel some ownership over this space, and to see Morrissey end his autobiography on an image outside this theater, where he has just played a show, which must have been one of the last shows held there before the venue was shut down, well it made me smile:

"For a year's-end concert at the Congress Theater in Chicago, the audience heaves with responding kindness, and I am immobilized by singing voices of love.

All along, my private suffering felt like vision, urging me to die or go mad, yet it brings me here, to a wintry Chicago street-scene in December 2011 - I, a small boy of 52, clinging to the antiquated view that a song should mean something, and presenting himself everywhere by way of apology. It is quite true that I have never had anything in my life that I did not make for myself.

As I board the tour bus, a fired encore is still ringing in my ears, and then suddenly a separated female voice calls out to me--full of cracked now-or-never embarrassment above the still Illinois winter atmosphere of midnight, and it was dark, and I looked the other way." (457)

Such a great fucking ending. And you have to love the "still Illinois" line.

Morrissey does that a lot in this book--inserts lyrics or song titles into lines. And there's a lot of alliteration. But as I just mentioned, the real power in this book comes in the multitudes it contains. Everyone will find something extremely personal (like I found in its ending) within it, and the only ones that will fail to be touched will be those that, for whatever reason, are predisposed against the author himself. And why would anyone be predisposed? Because we don't like whiners. But as a whiner himself, I can say that the world has needed Morrissey, and is richer for his presence.