Wednesday, July 18, 2012

The Moral Compass of the American Lawyer - Richard Zitrin and Carol M. Langford

The Moral Compass of the American Lawyer, published in 1999, has not become obsolete. Almost everything in this book is still true. However, I should note that it's not exactly my place to verify these stories as true. I can only confirm by circumstantial evidence that they are true, and I think the only people that would seriously denounce this book are lawyers at big firms.

This is probably the main reason I liked this book: while it has many targets, big law firms face the firing squad front-and-center. I have been attacked in the past for "hating journals" just because I failed to make one and perhaps I only "hate big law firms" because I failed to get recruited by one. That may be so--but apart from all of their other various modes of deceit and greed--recruiting is the only aspect I've been able to observe (albeit from a distance). I was told my friend didn't get a call-back from Sidley, even though she was great, really great, because they just met too many other great people at OCI. Well they do not even come to BLS. They do go to NYU. Thus there is approximately 0.01% chance that I can work at Sidley if I go to BLS. That 1/100th of a percentage point is there in case I was #1 in my class and somehow managed to get a "special" OCI interview, which must happen sometimes. I am not great. I write blog posts making foolish statements. It shows remarkable immaturity, what I write. It's frankly juvenile. Clearly there is no place in the culture of that firm for me. I lack the requisite fastidiousness. I like to cite cases specifically because one of the people involved happens to be named Batman (seriously). I wear Polos and dirty Converse to work because it's 100 degrees outside--I only wear a suit when I need to go to court. I put on Open Mic events at BLS just so I can hold a microphone and force 15 people to listen. I run for President of BLS (of the SBA) and tell people that a vote for me is a vote for anarchy. I get 33% of the vote. I have not cut my hair since February. Nor have I dry-cleaned my suits since May, nor have I ever ironed one of my shirts since starting law school. I am a penny-pincher, and I hate most people. On the other hand, I have a tremendous singing voice.

There are probably those that don't think big firms are evil, but are merely stuck on a course from which they cannot divert. Take for example the 1L Luncheon I went to about a 1 1/2 years ago with Paul Weiss. A partner said, "Sorry, we know it's not fair, but we can only consider people in the top 10%. I know it's not right, but that's just the way it is." So at least they have the decency cursorily apologize for their elitism.

The only thing "outdated" about The Moral Compass of the American Lawyer is its (fair) absence of material on e-discovery. E-discovery is now what people like myself dream of doing with their lives. The proliferation of contract attorney positions shortly after the publication of this book has opened up a few more job opportunities for graduates while effectively shutting them out from far more. In the name of economic efficiency and flexibility, law graduates face precarious employment on a more dramatic scale than in years past.

Chapter 3, "Power, Arrogance, and the Survival of the Fittest," is this book's foray into the world of discovery, and it does at least drop a hint about the future:

"As the size and scope of the nation's largest law firms increased, so did their concentration of power, leading to what many see as the death of the law as a profession. The efforts of many law firms to use discovery not as a means to an end but as a profit center underscores this feeling. Many stories like this one circulate in trade journals or on the Internet: A senior corporate counsel interested in moving back to private practice suggested to the senior partner of a large law firm that he would bring with him case-settling skills that could help avoid years of unnecessary discovery. But the partner explained clearly and bluntly what a terrible idea this was, because it would interfere with the firm's principal moneymaker--discovery battles." (61)

On a broad scale, this is a book about Ethics and Professional Responsibility, and the ways in which lawyers more often than not use the rules as guideposts for what they can get away with, rather than what they must refrain from.

This book is also largely about how criminal defense attorneys face a moral dilemma when confronted with knowledge that their client is guilty. This is one of the more interesting parts of the book.

Some of the other topics covered include class action lawsuits, tort reform, secret settlements, "ambulance-chasing," the Rules of Evidence and psychological persuasion of the jury, and whistle-blowing. All of them are fairly interesting and the book is more entertaining than The Lawyer Myth, for example (reviewed here http://flyinghouses.blogspot.com/2009/11/lawyer-myth-rennard-strickland-frank-t.html), but not as good as 1L (reviewed here http://flyinghouses.blogspot.com/2009/07/one-l-scott-turow.html).

I recommend this book primarily for two reasons: (1) It seems like a good substitute for Professional Responsibility, if one plans to take the MPRE before taking the course (as I am); (2) While using some of the tactics from the chapter on "misleading the jury" may not go over well with a professor of Trial Advocacy, they may be useful to know for actual trial attorneys. However, this book will not help you make it onto Moot Court.

Nor will it help you make it onto a Journal. While it does provide reasonable citations in the back of the book, there are no footnotes. This makes it a much more pleasurable read, but also apparently leaves many of the statements nothing more than pure speculation. I do not doubt the truth of most of what Zitrin and Langford expose--I am sure their personal experience has taught them certain "truths" that won't be validated by scholarly articles--however I could see how certain academics could question the integrity of this book.

There is a lot about the O.J. Simpson Murder Trial in here. And there are also more than a dozen lurid stories about lawyer misconduct and corporate wrongdoing. So if you need further proof that society is corrupt practically beyond repair, you may find this book useful.

Moreover, I like almost anything that has to do with Lincoln:

"Even our most sacrosanct hero is not immune. Abraham Lincoln's most celebrated case was the defense of 'Duff' Armstrong, in which Lincoln used an almanac to prove that the key eyewitness could not have seen by the light of the moon because the moon had already set when the crime took place. But what is often omitted in the telling of this tale is that 'Duff' Armstrong was almost certainly guilty." (30)

There's lots about Products Liability and Mass Torts and hourly billing and the adversary theorem--so much that you may feel you've already read a certain section. But Zitrin and Langford do make slightly different points all throughout their book, though they all center around the same concept: change must come!

At the end, like certain law review articles, they offer proposals for reform. Of particular interest is the reforms they suggest for law schools. They first point out that Professional Responsibility (while now required) is hardly the class it could be, and that students often don't get very much out of it. They also point out that courses that teach interviewing and negotiation skills should become part of the required curriculum. They also suggest an increase in clinical programs. BLS has done all of these, though Interviewing & Counseling and the Negotiation Seminar are not required. (They are taught by one of the legends on our campus though, and worth taking). Skills credits, however, are required, and may be satisfied by the Clinics, which students are all too happy to take, since it takes about 80% of the anxiety of searching for an internship out.

Interestingly, they do not advocate abolishing the curve. While they point out problems with the "adversary theorem" they give its role in legal education short-shrift. They do say that there are certain good things about the adversary theorem, but in school, there is very little positive I can say about it except that sometimes it makes people like myself feel okay about themselves when they make statements like, "We are going to steal all of the A's in this class! We are going to befriend the smartest people in the class so we will be the only ones getting A's!" (It never works.)

Few will say that the legal profession has improved since 1999, but I do believe that changes are coming. At the very least, students frustrated with the current scenario will one day practice, and may try to be the change they'd like to see in the profession. Slowly but surely, people like the jerk at the Cubs game that told me to shut up when I mentioned Ken Feinberg to my sister when she brought up the possibility of a CTA Train being bombed by terrorists during the NATO summit, will care less about mocking the public perception of what lawyers do and will realize that we are people too, just trying to make a living. I also won't have to come up with harsh rejoinders to such people like, "I hope you die intestate."

Friday, July 6, 2012

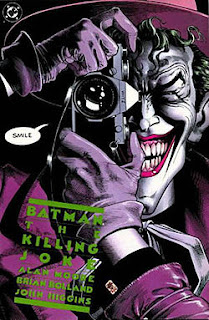

The Killing Joke - Alan Moore and Brian Bolland

The Killing Joke is not a graphic novel in the same sense as The Dark Knight Returns. For one, it is about 40 pages long. It is basically like one-quarter of The Dark Knight Returns. Having said that, it's arguably better than any one of the four parts of that book.

The story is short and sweet and to the point and while I was afraid of "spoiling" The Dark Knight Returns, and therefore didn't want to even name the villains that Batman faces in that story, I have mentioned it to several people and most of them just admit that they'll never read it anyways, why don't I just tell them? I do, but I'm doing them a disservice. They don't know what they're missing.

I was going to buy The Killing Joke until I saw that it was $18 and could be read in one sitting at Barnes & Noble. One night last week en route to picking up some take-out on a Friday night, I sat down up against the window of second floor B&N in downtown Evanston and ran through the book in about 30-45 minutes. It's brilliantly written, hilarious, very sad, slightly heartwarming, and perverted as hell. Once again, definitely not a book for little kids.

What is most interesting is that the story is basically the Joker's, and Batman plays more of a supporting role. Literally!

The story opens up with Batman saying, "You know, I really, really don't want to, but one of these days, one of us is going to have to kill the other." (Note: I may be conflating this line with The Dark Night Returns, but the idea that Batman sympathizes with the Joker to a certain degree is accurate.) Batman really doesn't hate the Joker as much as he does in other stories. What he feels for him is more akin to pity. And the opening of the story certainly lends a sympathetic air to the Joker.

This is because it tells his "origin story" and it's so sad. This is what makes The Killing Joke a real masterpiece (even though Alan Moore later said that he did not think it was very good, and even though most people agree that it does not rise to the level of Moore's other 3 famous graphic novels - Watchmen, V for Vendetta, and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen--all of which have been turned into movies ranging from mildly disappointing to downright disastrous).

The Killing Joke is, in a sense, "turned into a movie" if one combines Batman (1989) and The Dark Knight (2008). There was much talk in The Dark Knight about how you could not be sure of the Joker's true origin--but Batman left nothing to the imagination. I think the truth is that it's a combination of the two.

First, yes, the Joker was married. However, he did not cut his wife's face. (He does disfigure Alicia, in Batman, but that is irrelevant here). Instead, he works as an engineer at Axis Chemicals, and he decides that he wants to do what he really loves--which is to make people laugh. So he quits his job and starts trying to work as a stand-up comedian--and is a horrible failure at it. In one scene, he and his wife (who has recently become pregnant) sit in a restaurant and dwell upon their impoverished life since he quit his job. Needing money, he decides to accept an offer from the Mob, who want him to help them break into a building next door to Axis Chemicals (note: I am lifting this is off of Wikipedia--my memory is not so sharp and I don't own the book--but apparently it's a "card company"--now one would assume that means credit cards, but it could actually be a card manufacturing facility, which is certainly more appropriate).

Then, the police informs him that his wife has just died in an accident. The Mob forces him to go forward with their plan even though he has been traumatized. They put a Red Hood on him apparently to disguise him (though it seems more like a trope used to reference the real introduction of the Joker in Batman comic books--in 1951 in the issue "The Man Behind the Red Hood."). Batman comes in to save the day, and the Mob is dispersed, but "Red Hood" is left standing there. Having just lost his wife and unborn child, having lost out on the money he was going to get from the job, being a failure as a comedian, being trapped in a corner by Batman, he decides to commit suicide into a vat of acid.

Second, yes, the Joker was disfigured in a vat of acid. While this does not explain his scars in The Dark Knight, this is a story that I like much better, because of how the rest unfolds. The Joker, now in present day, decides to play a "big joke" on Gotham City. The set-up for that Joke is to break into Commissioner Gordon's home.

He breaks in, and he kidnaps his daughter (who is perhaps in her late-teens to mid-twenties--it's unclear). He takes her into a room, strips her naked, cuts her, and takes pictures of her being tortured. Commissioner Gordon is also kidnapped and brought to a funhouse. He is also stripped naked and put into a "freakshow" cage and forced to watch a slide-show of the torture of his daughter. After only a short while, he goes insane. This is the Joke: if a person is just pushed and pushed and pushed--just hard enough--they can cross the line from sanity to insanity.

It is here--when Batman arrives--that the real theme of the story emerges: all it takes is "one bad day" to drive someone insane for the rest of their life. Some people can be redeemed--like Batman. And some people cannot. But Batman believes that the Joker has to have a chance. After Batman arrives and frees Commissioner Gordon and reunites him with his daughter, the Commissioner tells him not to kill the Joker but to bring him in to "show him the way we do things."

At this point the stage is set for the final scene, with the Joker taunting Batman that perhaps his madness is also attributable to "one bad day." He then claims that there is nothing worth living for and gives a short speech about the virtues of nihilism and tells Batman "the Joke."

"See, there were these two guys in a lunatic asylum... and one night, one night they decide they don't like living in an asylum any more. They decide they're going to escape! So, like, they get up onto the roof, and there, just across this narrow gap, they see the rooftops of the town, stretching away in the moon light... stretching away to freedom. Now, the first guy, he jumps right across with no problem. But his friend, his friend didn't dare make the leap. Y'see... Y'see, he's afraid of falling. So then, the first guy has an idea... He says 'Hey! I have my flashlight with me! I'll shine it across the gap between the buildings. You can walk along the beam and join me!' B-but the second guy just shakes his head. He suh-says... He says 'Wh-what do you think I am? Crazy? You'd turn it off when I was half way across!"

The ending has been open to speculation, but I think I am reasonably sure of the way it ends. Note that I would recommend both The Killing Joke and The Dark Knight Returns very highly--but that The Killing Joke should be read first. Philosophically, I think it is the most interesting story in the bunch, and since the Joker has always been my favorite character (indeed I will play him in Batman in Brooklyn) I am naturally drawn to this book. As the present-day Joker and the "pre-suicide" Joker are presented alongside one another, one feels sympathy for the character in one instant, where all he cares about is taking care of his wife and making people laugh, and one feels derision (or maybe, catharsis?) as he mutilates and takes pictures and does who-knows-what else to the Commissioner's daughter. This duality then, compared with Batman, who is psychologically "one" with the Joker, but morally opposed to his view of life--who takes his bitterness out on the world, making it a more miserable place, rather than trying to make it a better place by ridding it of such evils--makes the story something of a meditation on human existence.

I was not going to pay $18 for the deluxe edition, but I would consider getting Alan Moore's DC Universe compilation, as this is apparently included in it, and it is a story that I would like to revisit some day in the future. This has also been a very pleasurable "research" experience, as I hope to utilize some elements from both The Dark Knight Returns and The Killing Joke in Batman in Brooklyn. I may go back to Barnes & Noble today and read some more Batman comic books, actually. That sounds like a pretty good idea, yeah....

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)