Showing posts with label Jonathan Franzen. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Jonathan Franzen. Show all posts

Sunday, March 29, 2015

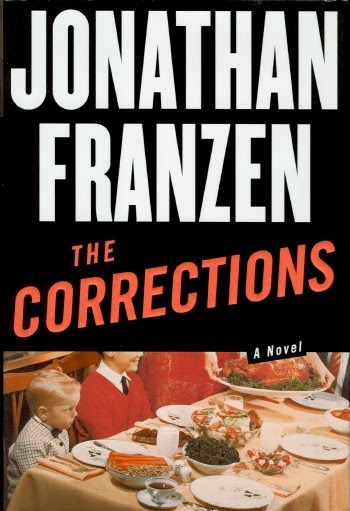

The Corrections - Jonathan Franzen (2001)

Oeuvre rule: I have only previously read How to be Alone, which came out a year after this. I enjoyed it very much, while I thought Franzen sometimes went on too long and sounded a bit pretentious and cranky. Some of the material intimates Franzen's raison d'etre in The Corrections--i.e. "this is what I was trying to do" or "this is what I was going for..." I would like to revisit it in light of those comments, because I'm going to agree with the rest of the world and slap huge compliments on this novel. Oprah, I'm not going to read everything in your book club, but you got it right with this one. (No comment on Franzen's disavowal of that institution--except my belief that he regrets that in retrospect.) I don't have a book club, but I do name those I consider the best books reviewed on Flying Houses, and this one makes the list.

Recently, this novel was named the #5 novel of the 21st century so far, and overall it is a very fine piece of literature indeed. I have minor complaints: the unfortunate media-driven obsession with sex in American society is transplanted into these pages, and Franzen occasionally goes off on a super-long tangent. The second complaint is also a compliment, however, and I realize it is hard to produce an item designed for entertaining the masses without appealing to baser instincts.

The most notable thing about this book are the extremely long chapters. There are only a few: "St. Jude" (9 pages), "The Failure" (120 pages), "The More He Thought About It, the Angrier He Got" (99 pages), "At Sea" (97 pages), "The Generator" (117 pages), "One Last Christmas" (99 pages), and "The Corrections" (5 pages). 7 chapters in 570 pages seems unwieldy, but this is not a criticism. It serves to break the book up into recognizable sections. "St. Jude" and "The Corrections" are short introductions and conclusions to the novel. "The Failure" is about Chip. "The More He Thought About It..." is about Gary. "At Sea" is about the cruise that Enid and Alfred take. "The Generator" is about Denise. And "One Last Christmas" is about the family together for that event. I found much to enjoy about each of them. The book is a consistently pleasurable read.

The plot? The major device is Alfred's failing health--he has dementia and Parkinson's disease, sprinkled together with Alzheimer's. He is in his late 70's or early 80's. He worked as a railroad engineer his whole life and raised his family as pitch-perfect members of the middle class. He is married to Enid, who is constantly trying to put on a happy face and make everyone around her believe that her family is perfect. Their oldest son, Gary, is a successful bank executive in his early 40's, married to an attorney who has gone into public interest work because they don't need the money, with three kids. The middle child, Chip, is an anti-establishment English PhD pushing 40 who has recently fallen on hard times after a good teaching job, and is trying to finish a screenplay. Denise is a chef, but really "culinary master" seems more accurate, 32 and divorced, going through a transitional period. Enid and Alfred come to visit Chip in New York City before embarking on a cruise along the Canadian coast. Denise comes to visit from Philadelphia the same day, and Enid pushes the idea of bringing everyone back to the family house for "one last Christmas," because Alfred is losing his lucidity.

The first aforementioned "long tangent" occurs during these preliminary introductions. Out of nowhere, seemingly, Franzen stops the narrative and tells the entire story of Chip's rise and fall as a college professor. It was just as engaging, so I didn't mind, but it challenged my expectations. One other thing I wanted to mention about Chip is that he is the most overused character in all of modern literature: the struggling male writer in his 30's. I felt like I was reading about Nate or Guert (in his younger days) or even Nick (obviously to a lesser extent)--but while I am sure there are many more examples to be had of this "type," Franzen paints him as more of an unpredictable "bad boy" such that he feels more real, behaving impulsively and making bad decisions.

While Franzen's prose is remarkably pristine, I did come across one passage that made me believe he was not godlike, and could have put in a couple more minutes of research:

"The clerk laughed in a way that was the more insulting for being good-humored. But then, Chip had reason to be sensitive. Since D---- College had fired him, the market capitalization of publicly traded U.S. companies had increased by thirty-five percent. In these same twenty-two months, Chip had liquidated a retirement fund, sold a good car, worked half-time at an eightieth-percentile wage, and still ended up on the brink of Chapter 11. These were years in America when it was nearly impossible not to make money, years when receptionists wrote MasterCard checks to their brokers at 13.9% APR and still cleared a profit, years of Buy, years of Call, and Chip had missed the boat. In his bones he knew that if he ever did sell 'The Academy Purple,' the markets would all have peaked the week before and any money he invested he would lose." (103)

Now it is technically allowed for an individual to file Chapter 11 (see Sheldon Toibb, proper citation way too fucking lazy to track down), but that is rare. It would be most proper to write Chapter 7 here, as Chip would not be a good candidate for Chapter 13 at this moment. Perhaps Franzen meant to characterize Chip as a business, but I highly doubt it and digress.

From there, the book shifts its focus to Gary. Gary is somewhat mysterious throughout the beginning of the book, referenced by all the characters but silent, so his prominence in the chapter is noteworthy. The idea of what the novel will be about is completed here, basically. Gary is shown working in a darkroom, developing photographs of his family for an epic album that he will give everyone for Christmas, while his youngest son Jonah enthuses about The Chronicles of Narnia. His two older boys play outside with his wife, Caroline, and seem to like her more. Gary resents this, and calls her out for lying about a minor injury that she suffers while playing with them. This happens when Enid calls him and asks if they will all come for Christmas. Caroline refuses to visit his parents, and Alfred does not feel comfortable staying at their house for more than 48 hours. She pretty much comes off as a huge bitch when she explains why:

"'The truth, Caroline said, 'is that forty-eight hours sounds just about right to me. I don't want my children looking back on Christmas as the time when everybody screamed at each other. Which basically seems to be unavoidable now. Your mother walks in the door with three hundred sixty days' worth of Christmas mania, she's been obsessing since the previous January, and then, of course, Where's that Austrian reindeer figurine--don't you like it? Don't you use it? Where is it? Where is it? Where is the Austrian reindeer figurine? She's got her food obsessions, her money obsessions, her clothes obsessions, she's got the whole ten-piece set of baggage which my husband used to agree is kind of a problem, but now suddenly, out of the blue, he's taking her side. We're going to turn the house inside out looking for a piece of thirteen-dollar gift-store kitsch because it has sentimental value to your mother---'" (185)

I have to say that Caroline is probably the least sympathetic character in the book. In one sense she may be rational. Her husband's family is crazy, and she wants her family to be healthy and emotionally stable. But the reader feels very bad for Gary, when she seems to think that this fight over Christmas is going to lead to their divorce. Unfortunately, this is not a very charitable depiction of an attorney.

Much of this chapter is about Gary's fear of anhedonia--basically, depression. Lack of interest in things. But then, the end is this long shareholder's meeting of the Axon Corporation, which has offered Alfred $5,000 for his patent on a process for developing pharmaceutical anti-depressants, and which is coming out with a drug called Corecktall. Later on, Denise and Enid try to get Alfred on a regimen, because it may be able to cure his condition. While I would never suggest this chapter is "bad," I must admit that while I found certain parts of it highly enjoyable and stimulating, on the whole it was the least memorable section of the book.

"At Sea" details the cruise that Enid and Alfred take, and is fantastic from start to finish. It reaches its pinnacle in the conversation between Enid and Sylvia, a woman she meets while sharing a dinner table on the cruise, whom she intuits will either be an arch-nemesis or a friend. The two women spill out all their feelings as they continue to have "just one more." I do not want to spoil it.

Later, Enid is offered a drug called Aslan by a rogue doctor (who shares his name with a Simpsons character, albeit with different spelling) on board, and I feared that the book was turning into a rip-off of White Noise, which is now turning thirty years old and remains an absolute classic of the late 20th century. Thankfully, Franzen seems to recognize this (indeed Don DeLillo even offers a blurb in praise on the back cover), so this scene ends up being a mere homage to White Noise. Maybe it's not and I'm crazy but if you've read that book, you must admit that Aslan and Dylar are essentially identical plot devices:

"'We think of a classic CNS depressant such as alcohol as suppressing "shame" or "inhibitions." But the "shameful" admission that a person spills under the influence of three martinis doesn't lose its shamefulness in the spilling; witness the deep remorse that follows when the martinis have worn off. What's happening on the molecular level, Edna, when you drink those martinis, is that the ethanol interferes with the reception of excess Factor 28A, i.e., the "deep" or "morbid" shame factor. But the 28A is not metabolized or properly reabsorbed at the receptor site. It's kept in temporary unstable storage at the transmitter site. So when the ethanol wears off, the receptor is flooded with 28A. Fear of humiliation and the craving for humiliation are closely linked: psychologists know it, Russian novelists know it. And this turns out to be not only "true" but really true. True at the molecular level. Anyway, Aslan's effect on the chemistry of shame is entirely different from a martini's. We're talking complete annihilation of the 28A molecules. Aslan's a fierce predator." (318)

"The Generator" comes next, and for me it was the strongest section of the book overall, from start to finish (thus, "At Sea" combined with "The Generator" is certainly the strongest stretch of the book). It is Denise's chapter, and she is probably better developed than any other character. She spends her last summer before college working at Alfred's railroad company, goes to Swarthmore, and drops out not long after, discovering a love for culinary art. She marries a man much older than her while serving as his sous-chef. They get divorced not long after, and the major plot of the section is set into motion. Paid a generous salary by a benefactor, she travels through Europe to sample the cuisine, and returns to open her own restaurant in a massive building previously owned and utilized by the Philadelphia Electric Company.

Later this same benefactor (Brian) gets involved with a film project, and Stephen Malkmus is name-dropped as a person who would eat dinner with him at fancy New York restaurants, seemingly as a technical adviser. This really came out of nowhere, and it's particularly ironic because the previous book I reviewed here thanked "Steven Malkamus" in the acknowledgements section. I really wanted to point that out previously (was it just sloppy editing or some kind of weird SM Jenkins joke?). There is also this reference, which was prescient in 2001:

"Their few real differences came down to style, and these differences were mostly invisible to Robin, because Brian was a good husband and a nice guy and because, in her cow innocence, Robin couldn't imagine that style had anything to do with happiness. Her musical tastes ran to John Prine and Etta James, and so Brian played Prine and James at home and saved his Bartok and Defunkt and Flaming Lips and Mission of Burma for blasting on his boom box at High Temp." (349)

Prescient because, Mission of Burma was primed to come back about a year after this novel was published, and because the Flaming Lips were about to "peak."

The last large section of the book, "One Last Christmas," wraps up the story in relatively satisfying fashion. There is one particular sentence that almost made me want to cry--when Enid says, "This is the best Christmas present I've ever had!" There are a few strange moments at the end, though, and Franzen definitely does not arrange a conventional denouement. There is one seriously WTF moment (I will just say the word "enema" and anyone who has read it will know what I mean) that I don't understand, unless it's just supposed to be sort of icky and disturbing and nothing more.

The closing eponymous chapter reminded me of the ending to Buddenbrooks, which is also referenced on back cover in a blurb by Michael Cunningham (in the same breath as White Noise)--that is, it feels oddly unceremonious, but appropriate. There is a short dialogue about whether being gay is a choice and a reference to Six Days, Seven Nights. And then there is a type of "where are they now?" conclusion.

I've failed when it comes to highlighting the craft of Franzen's prose. I've picked out really random passages that I found notable for idiosyncratic and insignificant reasons, and I've avoided certain passages to preserve the pleasure of their discovery. Rest assured this entire novel is well-written. There are probably 10-15 pages of sentences included throughout the book that annoyed me for some reason, but they do not detract enough to remove it from its rightful place as one of the best books reviewed on Flying Houses. I just hope this review has done it justice.

Sunday, August 3, 2014

How to be Alone - Jonathan Franzen (2002)

I picked up How to be Alone at the Printer's Row Lit Fest, so it shares the dubious honor of being the second book after Rick Moody's Purple America to be purchased there and reviewed here. I liked Purple America and I liked How to be Alone but for different reasons. How to be Alone is a book of essays, and I don't know, I just kind of like reading essays. Let me put it this way: I prefer to read "essays" over "articles," and I hope that my posts on Flying Houses are considered "essay-like reviews" rather than "article-like reviews." But I digress - we must discuss the author.

The only time I read anything by Jonathan Franzen before was when I read a chapter from The Corrections that was re-printed in an anthology released for the 50th anniversary of The Paris Review (ironically, also purchased at the Printer's Row Lit Fest(!) - a decade ago when it was called the Printer's Row Book Fair). I didn't really get into it. So I never checked out that novel, or anything else by him. But he seemed like the real deal after Freedom got so much attention so I figured I should give him a chance when I saw this book for $5.00. And after reading it I will definitely check out more of his work.

But I can't go on without mentioning that I was put off by him before because he seemed like a kind of vanilla great writer--doing everything right, but lacking the ability to really engage the reader--from that little excerpt I read in that Paris Review anthology. Mainly I compared that with "Little Expressionless Animals," a short story by David Foster Wallace that was also in there and is probably the best (and only) thing I have finished by him, and decided that Franzen just wrote pretentiously.

***

The book starts off on an almost impossibly high note with "My Father's Brain." This is a remarkable essay that should be anthologized for any collection of 20th or 21st century writers studied by high school students (it could almost be an essay by Richard Selzer). Franzen ties together autobiography and science to produce an extraordinary tribute to his father that is highly emotional as well as educational. Having lost a grandmother to Alzheimer's disease, it was especially poignant for me when he mentioned how his father could still recognize the people around him as familiar, but could not identify their relationship to him. To be clear, the last time I saw her before she went to a nursing home, she referred to her son and his wife (who had moved in with her to care for her) as two nice people who were letting her stay with them for some unknown reason. Franzen's father similarly retained familiarity with his family members, but probably only thanked them for coming to visit in the nursing home because (apparently) Alzheimer's patients retain their manners and politeness, and other learned, ingrained social pleasantries. This, along with several other observations and scientific hypotheses, tells the reader everything they need to know about Alzheimer's. But what makes this essay even more amazing is the way Franzen branches off to discuss the nature of memory, and how writers employ it:

***

Before I go on, a confession: it has taken me a very long time to write this review. Not because I have complicated feelings about it, but because I've been lazy. Also I couldn't find a good quote from the first essay, so we move on.

"Imperial Bedroom" comes next and at this point I need to say several things: (1) that is the title of an Elvis Costello album; (2) that is almost the title of a Bret Easton Ellis novel; (3) a few days after starting this book on June 30, 2014, Bret Easton Ellis linked to an old interview he did on Facebook which referenced the most infamous essay in this book and also commented on Donna Tartt in June 1999; (4) this essay is about the Starr Report and was published in 1998; (5) this essay references the "zone of privacy" codified by the Supreme Court in the late 1800's, (6) this essay feels dated in a very charming way, like many of the other pieces in this book. I will get more into this later. But basically, this essay was o.k.:

"Walking up Third Avenue on a Saturday night, I feel bereft. All around me, attractive young people are hunched over their StarTacs [!] and Nokias with preoccupied expressions, as if probing a sore tooth, or adjusting a hearing aid, or squeezing a pulled muscle; personal technology has begun to look like a personal handicap. All I really want from a sidewalk is that people see me and let themselves be seen, but even this modest ideal is thwarted by cell-phone users and their unwelcome privacy. They say things like 'Should we have couscous with that?' and 'I'm on my way to Blockbuster.' They aren't breaking any law by broadcasting these breakfast-nook conversations. There's no PublicityGuard that I can buy, no expensive preserve of public life to which I can flee. Seclusion, whether in a suite at the Plaza or in a cabin in the Catskills, is comparatively effortless to achieve. Privacy is protected as both commodity and right; public forums are protected as neither. Like old-growth forests, they're few and irreplaceable and should be held in trust by everyone. The work of maintaining them gets only harder as the private sector grows ever more demanding, distracting, and disheartening. Who has the time and energy to stand up for the public sphere? What rhetoric can possibly compete with the American love of 'privacy?'" (53)

Okay, I'll admit sometimes I don't get exactly what point Franzen is trying to make, but let's just say he sounds like a curmudgeon in 1998 and he must totally want to kill himself with the state of things in 2014, as do I. So I make this offer to him: the next time he is in Chicago, he should contact me and we should take the El together and yell at everyone staring down at their phones. [Note: I have absolutely no problem with people reading Flying Houses on personal electronic devices].

The aforementioned infamous essay comes next. "Why Bother? (The Harper's Essay)" is one of the main attractions of this book, but not for the right reasons. I am sure there are plenty of people that would defend this essay as a "tour de force" and one of the finest essays about literature in the 1990's, but most people (and Franzen himself) probably consider it embarrassing and pretentious. Originally titled "Perchance to Dream" and published in April 1996, Franzen writes that when he actually opened up the magazine to read it, "I found an essay, evidently written by me, that began with a five-thousand-word complaint of such painful stridency and tenuous logic that even I couldn't quite follow it." (4) He "cut the essay by a quarter" and retitled it, and hoped "it's less taxing to read now, more straightforward in its movement." (5) It is 43 pages long and only wasn't taxing for me to read because I was stuck on an airline commute from hell that majorly comprised a 15 hour travel day. Also, it was not taxing because I kept waiting to see what ridiculous thing Franzen was going to write next. It is a gold mine for ridiculousness, but some valid points are made along the way.

As is the case for most of the essays here, it is spurred by something Franzen recently read. In this case it is the short novel Desperate Characters by Paula Fox published in 1970. (As a side note, Franzen name-checks many, many writers throughout this book, most of them a bit more obscure than the usual names mentioned. So it can be helpful also in terms of discovering new writers.) He writes a lot about how simple and beautiful this novel is and how symbolic it all is. He also writes about his first novel The Twenty-Seventh City and how his ideas of what literature should be shifted throughout the years. Now, I kind of want to read his first novel now, and I kind of get where he's coming from, even though I don't agree entirely with his stance. But maybe I'm confusing this with the later essay "Mr. Difficult," which I think is probably the strongest essay in this book ("Why Bother?" done right).

He writes a lot about Shirley Brice Heath and the observations she made about the reading public. He basically complains that nobody reads anymore. There's a lot of confessional stuff about his own writing, and he is usually pretty funny and occasionally lands solid moments of truth:

"Unfortunately, there's also evidence that young writers today feel imprisoned by their ethnic or gender identities--discouraged from speaking across boundaries by a culture in which television has conditioned us to accept only the literal testimony of the Self. And the problem is aggravated when fiction writers take refuge in university creative-writing programs. Any given issue of the typical small literary magazine, edited by MFA candidates aware that the MFA candidates submitting manuscripts need to publish in order to obtain or hold on to teaching jobs, reliably contains variations on three generic short stories: 'My Interesting Childhood,' 'My Interesting Life in a College Town,' and 'My Interesting Year Abroad.' Fiction writers in the Academy do serve the important function of teaching literature for its own sake, and some of them also produce strong work teaching, but as a reader I miss the days when more novelists lived and worked in big cities. I mourn the retreat into the Self and the decline of the broad-canvas novel for the same reason I mourn the rise of suburbs: I like maximum diversity and contrast packed into a single exciting experience. Even though social reportage is no longer so much a defining function of the novel as an accidental by-product--Shirley Heath's observations confirm that serious readers aren't reading for instruction--I still like a novel that's alive and multivalent like a city." (80)

I can see what he's saying about the MFA contingent (and I've complained about them several times over the years here), but I have to admit that, even though I can't consider myself part of that group (because I didn't get in to one of those programs, I'm more of the novelist that lives and works in a big city), I feel like I have to retreat into the Self, at least for the first couple major works. I feel like you can't truly understand the world until you've thoroughly examined yourself, and to give an idea of your perspective, you should publish at least a couple books that present it.

I seriously could write an entire blog post about each essay--and this one is a doozy for sure. But I have to move on as I'm doing the entire book and I think I've given an idea about the notoriety of this essay. Bret Easton Ellis said it wasn't a good essay in its original form, and I'm not sure if he thinks it's any better in its revised form, but it's certainly worth reading because you can't help but have strong feelings about it.

"Lost in the Mail" is an essay about the decline of the U.S. Post Office in Chicago in 1994. I loved it because so much of it is about Chicago, but as I was reading it I was paranoid that my city sticker wouldn't arrive that day in the mail, and that I'd get penalized for not having a new one on my windshield on July 1, but in reality they didn't start enforcing that until July 17th this year (and ironically, my city sticker arrived right after I finished the essay). As is the case for most of the essays here, it feels dated, but then again I don't live on the South Side. I feel like the Post Office has cleaned up its act over the past 20 years, but this is still an entertaining read because it is the first "live reportage" type essay here and feels like it's "from the front lines" and "an insider's look."

"Erika Imports" is probably the strangest thing in the book, but it's nice. It's like four pages long and is a brief nostalgia trip about the first summer job Franzen ever had, working for his neighbors. Maybe I only thought it was nice because it was so short though, and was such a counterpoint to the 30 page essay I was expecting.

"Sifting the Ashes" is a great essay about cigarettes. However, I was confused at the beginning as to whether Franzen had actually quit at the time he was writing it. Again, he references a recent book he read, Smoke Screen by Philip J. Hilts. Though this essay was published in 1996, it doesn't feel that dated. The only thing that's changed is that cigarettes have become subject to much higher taxation and have been banned from most indoor establishments across the country. I feel like somebody needs to write an essay about marijuana right now so that in 18 years we can consider whether it feels dated.

"The Reader in Exile" is the 2nd example of the "quintessential Franzen essay" in this book, after "Why Bother?" You can guess what it is about. He references A is for Ox by Barry Sanders, but mostly talks about Being Digital by Nicholas Negroponte. I mainly remember this essay for Negroponte's relentless positivity about the rise of technology, and Franzen's skepticism. It makes me feel like Negroponte was an early proponent of the robo basilisk paranoia, but I digress.

"First City" is an essay about New York City. It is also about the nature of cities, and how they differ in Europe from the U.S. Some interesting comments are made about urban planning. He references Witold Rybczysnki's book City Life. Further comments are made about The Encyclopedia of New York City, which are entertaining. In general, this is a paean to New York as the most European city in the U.S. and it makes me want to write an essay titled "Second City."

"Scavenging" is probably the 2nd strangest thing in the book. He also gripes about new technology here, waxing nostalgic about his rotary phone. He kind of jumps all over the place in this essay, but he mostly writes about using outdated technology. And it is here that we reach a milestone. For I read this essay right before I accidentally destroyed my old laptop's screen, and felt very sad, but then felt very proud like I would blog on a semi-broken machine. And I did that for a while, but at this moment, this post is the first post being written on my new laptop.

"Control Units" is about super maximum security prisons, and is a really great essay, actually. It's not quite on the level of "My Father's Brain," but it's like a more compelling "Lost in the Mail." Basically, Franzen is in full-on journalist mode here again, and he makes some great comments about the prison system in a particular Colorado town, and though it was published in 1995, this is another essay that has only grown more true as time has gone on.

"Mr. Difficult" is my favorite essay in this book. It is mainly about William Gaddis. I have never read anything by Gaddis but it made me want to--sort of. Franzen gives Gaddis the highest compliments imaginable, but also openly admits that some of his later work is a mess. This is one of the most fascinating essays in the book because Franzen seems openly enthusiastic about the material, and his opportunity to make a statement about it. There is also the interesting revelation that the title of The Corrections is meant as a nod to The Recognitions. Franzen also writes about his failed attempt to write a screenplay, because somebody told him that his movie seemed to plagiarize Fun with Dick and Jane (which seems weird for some reason). He also talks about books that he couldn't finish. He references The Sot-Weed Factor, and that is another notable example of a book that I tried to read while starting this blog, but failed to review as "incomplete." I guess this is about a certain period of American authors. Franzen says he didn't particularly like any of them that much except for Don DeLillo and Gaddis. Generally, I liked what he did with this essay. Franzen seems to have a deep understanding of Gaddis's oeuvre, and I can appreciate an essay on this sort of subject matter.

"Books in Bed" is another essay that is kind of like "Imperial Bedroom" but is mostly about sex rather privacy. It is also about watching CNN in airports. He again references recent books he has read This time it is The Joy of Writing Sex by Elizabeth Benedict, which is a compilation of sex scenes in literature. Franzen seems to view the culture's obsession with sex, and literary sex scenes, as another indication of the sad state of the modern world. But along the way, as usual, he is entertaining:

"Until the Rules become universal, though, such comfort as can be found in the market economy comes principally from norms. Are you worried about the size of your penis? According to Sex: A Man's Guide, most men's erections are between five and seven inches long. Worried about the architecture of your clitoris? According to Betty Dodson, in the revised edition of her Sex for One: The Joy of Selfloving, the variations are 'astounding.' Worried about frequency? 'Americans do not have a secret life of abundant sex,' the researchers in Sex in America concluded. Worried about how long it takes you to come? On average, says Sydney Barrows, it takes a woman eighteen minutes, a man just three." (273)

"Meet Me in St. Louis" is the last longer essay in the book, and is about Franzen's experience becoming a member of "Oprah's Book Club" and how a promotional movie was shot in St. Louis about his life. It's awkward and is one of the other major highlights of this book. In a way, it is similar to "My Father's Brain" because it delves into personal details about his life and his parents. It's entertaining and emotionally engaging to see how a bigger promotional machine can twist the meaning of a work of art into something different than its meant to be in search of a bigger return.

The collection ends with a trip that Franzen took to see the inauguration of George W. Bush in 2001. It's breezy and short--only "Erika Imports" is shorter. But it makes a stronger impression than that essay. It reads like a combination of "Journalist Franzen" and "Skeptical Franzen." It seems like a reactionary piece to the Bush v. Gore decision, and it feels very raw and angry. Obviously your political views may tint how you view this essay, but it seems like the vast majority of Frazen's fans will not take issue.

On the whole, How to be Alone is a nice collection, and was worth buying for $5. I'm not sure I'll revisit it anytime soon (maybe in a decade, who knows), but it was a thoroughly entertaining collection that made me feel very literary for reading. Anybody that wants to be a well-respected author that sells a lot of copies should read this to see inside the mind of one of them. Franzen is generous in that regard. Still, I can't help but feel that 50% or more of modern-day writers may claim he is full of it and you don't need to live the way he does to write great books. I'm not sure how I'll review his fiction, but I hope to have the chance soon.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)